“Say ‘cheese!'”

Okay, but…why?

From the time that we’re children, we experience people telling us to say “cheese” when taking a photo. Many of us never question it until much later in life, if at all. Why say “cheese” when cheese has nothing to do with photography? With a bit of thinking, it’s easy to come up with an answer (the “ch” sound pulls the lips back, exposing the teeth, while the “ee” sound opens the mouth, pulling it into a natural smile), but because it becomes so ingrained in us, we usually just accept that we say “cheese” when taking a picture without really bothering to learn why.

Now imagine a world in which cheese no longer exists. Where food and people are scarce, so the process of making cheese has been lost. Imagine a girl learns from a book that people say “cheese” when they take pictures, and imitates it when she and her friend come into possession of a camera.

Now imagine that, after learning that cheese is a thing you say when taking pictures, the girls stumble across something that’s “cheese-flavored.”

What the heck are they supposed to think cheese even is?

This scenario is exactly what happens to Chito and Yuuri in Girls’ Last Tour, and serves as a microcosm that helps set up the world they live in. Their entire existence is built on artifacts of a lost time, some of which they understand and many of which they don’t: a hyperreal world.

Hyperreality is a term usually attributed to Jean Baudrillard, describing the inability of consciousness to discern between a simulation and reality. For example, on the street I live on, there are median strips that provide some welcome glimpses of landscaping in an otherwise fairly concrete-covered area. It took me over a year of driving down it almost daily to realize that some of the rocks in these median strips weren’t actually real. They were merely artifices put there to mask something (I’m still not sure what) more practical but less visually appealing. Modern urban infrastructures are completely filled with these pleasant-looking facades, such as oil rigs hidden all around Los Angeles. We’re able to completely miss that many things we’re surrounded by are simulations rather than something authentic, just because we don’t know that we should be looking for a simulation in the first place.

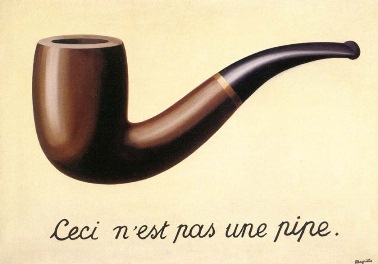

Hyperreality is often created through the use of “simulacra,” representations or copies of a real thing. These have always existed, of course, but modern society is completely inundated with them. Photographs, videos, paintings, etc. are all simulacra as is, but when you take into account that many of these are reproduced, recreated, or otherwise altered, you start to get a sense of how hyperreal the world that we live in is. Perhaps the best illustration of this is René Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images.”

The text, translated from French, reads “This is not a pipe.” This seems like a blatant lie, until you realize that no, it’s not a pipe. It’s a painting of a pipe–or in this case, a .jpg file representing a painting of a pipe. Yet our first response, upon seeing it, is to identify it as a pipe, simply because simulacra representing a thing have become so prevalent that we define them by what they represent. And all this without even dipping into meme culture, which is almost entirely based in copying, altering, and reapplying a template until any original meaning is completely lost.

This is all a very roundabout way of saying that, in the Information Age, information travels so fast and gets distorted so heavily, much of what we know is pure simulacra, devoid of any discernible origin. And in Girls’ Last Tour, which takes place in a post-Information Age world, even the simplest of knowledge is lost, but the simulacra remain. The world Chito and Yuuri exist in is full of echoes of simulations so far divorced from what they’re simulating that they have become their reality. Put in these terms, the sheer level of ignorance they have isn’t actually that far-fetched.

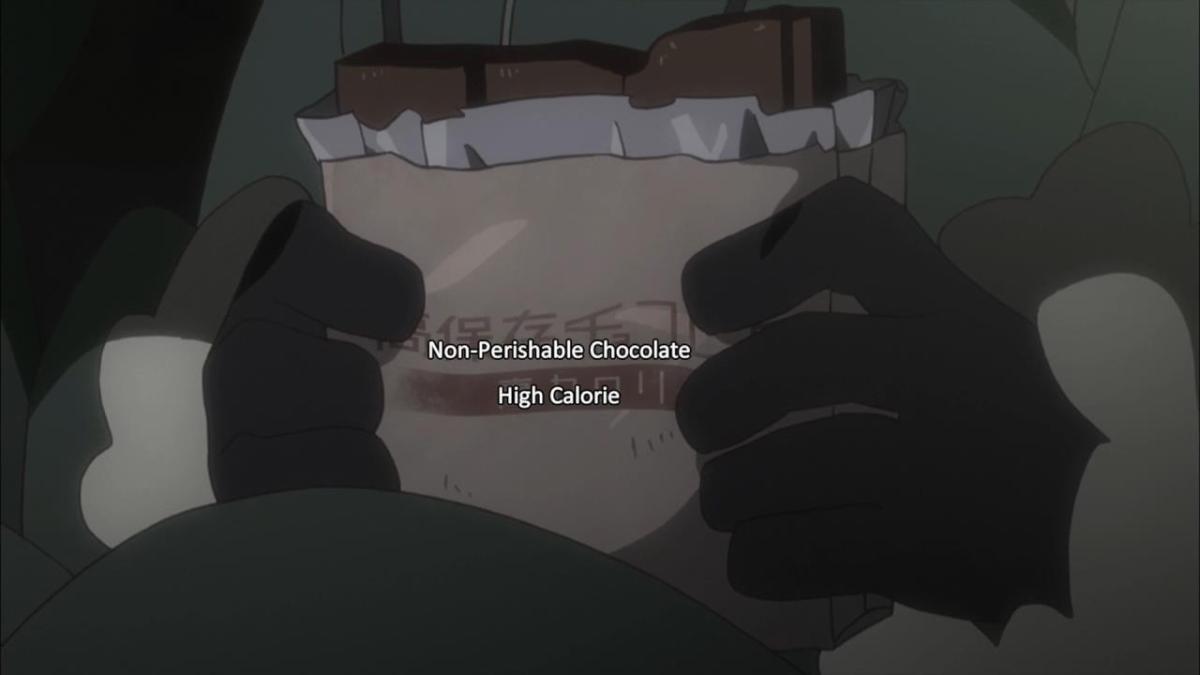

The hyperreality present in Girls’ Last Tour is often times very granular. One notable example of this bookends the anime. Early in the first episode, Chito and Yuuri find a box of supplies containing chocolate-flavored rations. Upon eating them, Chito remarks that she doesn’t know what chocolate even is. Then, at the end of the anime, the two come across an unknown sweet food that Yuuri identifies as chocolate-flavored. When Chito suggests that it might actually be chocolate, Yuuri brushes her off, saying it’s probably just chocolate-flavored. As Chito concedes, we’re shown an image of the packaging, showing us that what they’re eating is, in fact, genuine chocolate.

In addition to this and the aforementioned “cheese” example, where the girls only know cheese by its flavor and its relationship to photography, there are minor details that we as viewers would recognize as simulations (and thus learn more about the world) but Chito and Yuuri would not. The two fish they encounter are both unnaturally white and simple-looking, making them look somewhat “off.” Likewise, the potatoes the girls eat are pale, rectangular, and grow on vines, and while it’s possible there are varieties of potatoes like that, they’re unlike any I’ve encountered. Are these true potatoes, or has “potato” just become a term for a larger group of foodstuffs? Have these potatoes and fish been mutated or genetically modified somehow? These same questions also pop up when they encounter a creature they think might be a cat, which both looks and functions differently enough from a cat that we as viewers have no clue what type of creature it might be.

The ideas of hyperreality can often be very broad, touching on ideas like religion. On their way to visiting a temple, Chito runs into a statue they later discover to be a representation of a god. While in the temple, they get separated in the dark and cope with feelings of fear and loneliness before emerging into a well-lit, beautiful room, comparing both experiences to the afterlife, implicitly posing the idea that religion is a form of hyperreality as well, a simulation of a higher truth created to replace an absent one. This idea is emphasized by their conversation that the “heaven” they emerge into after their experience in the dark is a mere replica, filled with metal lotuses and fake fish swimming through glass. Yuuri expresses her disappointment at the “god” and “heaven” they encounter are just “plain old statues.” When Chito warns that she could be punished for that, Yuuri counters by pointing out that Chito knocked over one of the statues on her way here. Chito’s response? That it was just a “plain old statue.”

This hyperreality in religion is further emphasized by a later part of the manga, when Chito and Yuuri encounter strange creatures who are ingesting and neutralizing thermally unstable matter. These creatures bear a very striking resemblance to the god statues the two continue to encounter, but it’s unclear what exactly the nature of the creatures are. Are they machines? Aliens? Something else? Whatever they are, there were clearly people deifying them at some point, so it becomes impossible to view them through the lens of anything other than religion.

However, the most direct discussion of hyperreality in the series occurs when Chito and Yuuri visit a run-down fish-processing factory. There, they discuss what exactly a “living being” is, with Yuuri asking if a machine that could walk up to them and say hello (thus implying sentience), would count as a living being. Immediately after Chito attempts to dodge the question by saying that there aren’t any machines like that, a machine does just that. The machine goes on to prove itself able to hold a conversation, as well as explain that it is capable of empathy. When the two go swimming, Yuuri strips naked while Chito balks, stopping at her underwear, uncomfortable with being seen naked by “another person,” despite it being a machine. Throughout the rest of the factory storyline, they continue to treat these machines, which are imitations of life, as actual living beings, as they’re unable to distinguish between the simulation of life and the reality of it.

In addition, this portion of Girls’ Last Tour explains why there’s so much hyperreality in their world: because the whole world has undergone hyperreality. The robot explains to them that, while humanity was once subject to the environment, they chose independence of it, creating cities that served to artificially provide everything needed for life. The implications of this, as well as a few other moments in the series is that, between creating these artificial environments and a large-scale war, the environment of the planet was completely destroyed and became unable to sustain life. While the world of Girls’ Last Tour is certainly more advanced than our world, it’s clear that humanity’s attempts to control their environment, along with their disregard for maintaining the ecosystem of the world as a whole, are not that far removed.

Simulation can be a wonderful thing. Art simulates life in an attempt to reflect and elevate in a more meaningful way, as well as allowing for some often much-needed escapism. The ability to simulate environments allows us comfort year-round, and the ability to emulate flavors has resulted in all sorts of wonderful snacks. And even religion, assuming it too is hyperreal, can be a fantastic thing that provides people with comfort. But by showing us a picture of a fully hyperreal world, Girls’ Last Tour also shows us its dark side. If information moves so quickly that the basis is lost, we risk the destruction of meaning and culture. By attempting to modify the environment, we risk the destruction of the planet’s ability to support life. It seeks to warn us that, while simulation is fine, we must know our limits.